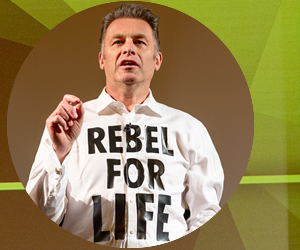

Delivering the annual BAFTA Television Lecture

January 27, 2020The Barbican, Tuesday 21 January 2020

He called on the television industry to make environmental productions carbon neutral within three years, to reduce television production’s impact on climate change and help highlight the truth about environmental problems our planet faces.

He opened his lecture with a powerful dystopian story to demonstrate how climate change could shape our future …

The Story

He will pitch precariously over the top of the ladder at the peak of the thousand bund and as he does so his last fingernail will break off and float out and away like a flake of fire ash . He’ll pull down his uveey and squint after his scale , watching it spiral on the salty updraft until that precious little piece of him softly melts into the smog and vanishes . All the younglings will lose their nails , most will shed their hair and many their teeth by the time they’ll be his age . He will be fourteen .

. . . . .

The descent was dangerous , the rungs swung lose and rusty and the wind smacked his face and tore at his smock for the long hour that he spat the brine and drank the tears that streamed from his sea-stung eyes , clambering down , a speck on that sheer face of steel and stone . He dwelt in the shade of this great dyke and at certain times when the grinding of the colossal tides quietened they knew the waves had sunk and the bravest of the well-fettled made this journey to try and see the sun .

He saw the old fishering man as soon as he landed on the naked shore , far out beyond the litter-slick bent forward with his fisher-stick , blobbed with great clots of spindrift , knee deep in the brown slosh , staggering to stand , on the sand , on that edge of the seas land . The figure lurched in the spume and he wondered again at his desperation , the ancient fool , with his ancient fisher tool , tugging its line through a fishless ocean with some hell-bent redemptive notion .

The base of the bund bore the work of the pre-ers , those with memories of all the gone-things . Tattooed there in tableaus of wave-worn paint were a menagerie of fantastic fables , slippery-shaped blue and grey creatures with giant swimming arms , with huge spouts of steam boiling from their backs , smooth and sleek , some leaping clear of frothy white water , others bent beneath with their babies curved between their tails . He gazed through the fug at murals of shining fish and traced his fingers over the mottled bodies of eight-legged devils with bulging eyes and found twenty tiny buttons prettily banded in orange and white , peeping from a tangle of ropey fingers nestled in a jumble of violet and yellow-green rocks . The paint had long peeled , these were the fading myths from the ‘Time of Trees’ .

Years before his mother had taken him to visit the tree . His father and brother had just died in the Third Famine and his sister had vanished before the gretchy had come . They’d transported all day and despite the fact they’d tokened their units the line of pilgrims was so long they’d turned back having only paused in confusion of the monuments silhouette .

Smaller than they’d been led to believe , the tree was broken into a wicked tangle , twisted , painful and sad . He blinked and squinted to spot what the mutterers said were real leaves and those sickly smudges behind the rain soaked plastic shroud were all he could remember of the worlds last tree . Except that it was on the transport back that the hoax about the bird had been newsed and the whole world screened-in to the follow the search . Nothing was found , they all knew the birds were gone , not even his father had seen a bird .

The fishering man staggered up the beach , rolling in the surf , broken by the sea and betrayed again by his half-witted hopes . So the boy trudged down and helped to drag him roughly across the plastic shore , filthy and stinking of the sea sludge , foaming from the mouth , retching against the poisons , his hands raw , pinkened with sores and blotched with rosy bleeds . He dis-entangled him from the coils of his fishering stick which danced spitefully in the gale and snapped on the rocks as the afternoon began to rot .

As on every other of his adventures over the bund the sun was not going to show , there was no horizon , a thin rusty strip lay where the slimy beige water blurred invisibly with the greying mud coloured sky and soon a long clammy night swallowed the two fugitives as they crawled into a cave at the foot of the rampart . He began shivering and the fishering man began vomiting . He spewed three times , the first brought forth his last meal of cud , the second a froth of bitter pus and the last a splash of blood , clots of which rubied his matted beard .

In the howling gloom as they shook and spat , the fishering man fictioned him that he’d watched the pre-ers artisting the ramparts when he was a youngling . They’d come in floaters from the outside , they were ancients but they had good fettle , they brought ladders and papers with artistry on them , and they’d copied the gone-things onto the grey slabs in swirls of brilliant colours . They’d had names for all those ghosts and he’d forgotten all but one . . . whales . The biggest monsters in their bestiary were called whales and one of the pre-ers facted that she had seen them living . She’d storied the younglings that whales lived in the sea but breathed from the air , that they transported all around the oceans , deep-downing and had a secret language of beautiful songs which they sang in warm blue waters , that they could leap into the sky , and had families and tribes and lived for hundreds of years . She storied that the pre-ers first murdered these whales for food , then broke their ears and then fed them plastics until they rotted inside-out and all died .

She storied that there were once so many different gone-things that no one could count them, and she’d shown them her skin which was painted with many fabulous creatures . The pre-ers smiled and called her the ‘Library of Life’ and they’d circled around her naked body crazily naming all her artistries whilst the younglings chincked in awe and wonder and cried ‘again , again , again’ . And so she storied until the sky went out and everyone stared up at their fresh glowing frescos in silence and the pre-ers promised to return and they packed their floaters and went out smaller and smaller . That night and for five more there were great storms and no-one ever saw those pre-ers again .

The morning air was thick and still and when he scaled the wall he was giddy with tiredness and hunger so rested frequently , hanging on the steel , his eyes closed , listening to his gasping heart . Halfway up his ascent the beach was still visible and he watched the tiny fishering man wrestling with his stick and striding out through the dreck , stumbling and rising until he reached the ribbon of oily scum where he cast his line , baited with his puke , into the barren sea . Beyond him he could see the carcasses of the final floaters , buckled and slumped , jumbled and lumped , their bodies rent all dressed in the mess of the plastic spent , by the pre-ers . They had killed everything , the gone things , his father , his brother and sister , the sea , the air , the land , the birds , the whales . Only the fishering mans hope and his grip on the ladder were beyond their hateful curse .

. . . . .

He ached , every cell in his body was groaning in relentless agony . He had survived the sixth famine but the seventh was going to kill him . He’d had no gretchy for two weeks and his cracked lips had drained the last of his water five days ago . It was silent apart from his failed door softly knocking and his ransacked room was revoltingly hot . They’d all either left or were dead . So he was alone in his cot , sweating , itching , coughing and lying in his stinking shit and piss . Every time he turned he’d crack the skin of his mess and choke on the stench , the rind peeled from his sores and the agony snuffed out his consciousness . He woke for the last time in a twilight and listened to his scratchy breaths and when he’d summoned the courage drew open his scratchy eyes to see that he could no longer discern colour . He recognised this as the point of his death and his last thought did not come randomly . He’d been dying slowly enough to have prepared for this moment .

And so he recalled his final climb in search of the sun , all those years ago when he had the fettle to scale the bund and sneak down to the beach . On the way up he’d been smothered in the smoke from the pyres of burning dead , the sweep of the spotty sickness had been thorough and thousands of younglings were dying , too many too quickly to transport , so they set them alight so outside their homes each dawn . And when he’d pushed on clear of the fatty stench of searing flesh he’d perched for a while on the dizzy top of the parapet and surveyed his world .

The foreground had been speckled orange and flowed lazy-grey with the fires fuelled with the burning younglings , the smoke rolled , softly veiling the black and brown sub-city slums , long lavender ribbons that thinned to a stupor in the east , where the their star should have risen , but where the light never set . That’s where the ever-glow of the mega-blocks and all their power-thirst bloomed orange , fat and heavy , with flickering lines of light , the lines where the lucky lived their lucky lives of luck , in the thickest of the muck , where everything was stuck , ground down , in brown town , in meltdown .

It was there that the millions had swarmed , whilst the world warmed , huddled close to their uninformed and denied-deformed desire to hide out in the anti-worlds , those concrete closets where they nurtured their skeletons and locked their truths away to roll and knead the greed , and quashed the need , of those who sought to intercede , denied extinction speed , and who now knelt captive , helpless before their machines .

Outside , the scum , the sweat and flesh , the lumpy-ugly , the fungus-eaters , the gretchy sick and hungry swarmed in futile starvation furies in their slump of sprawl , dirty and thick , moronic and sick . Born to die and just waiting . Wasting and waiting to be waste .

The fishering man had disappeared a few weeks later , presumably drowned or fallen from the ladder and been sucked away in the gloop . The boy had cautiously checked the cave expecting the reek of a corpse and there were signs he’d rested there , a pillow of plastic and the torn sheets he’d clothed himself in , handprints in the sand , the prop where rested his fishering stick and the signs of a small fire . A blackened circle of sand and close by a scattered pile of tiny flakes , silvery , shiny , glistening as if the old man had pulverised some glass . They sparkled emerald and sapphire in the light and shone bright grey in the shade . He flicked them and they floated and flashed , glittered and coated his finger in a shimmering crystal skin , a dust of diamonds . He’d twisted his hand and a deep smile came out of him as he loved their pretty twinkling . He’d sniffed them , oily and salty , with a warm bitter sting , like nothing he’d ever smelled before , nor ever smelled again .

. . . . .

And as his heart will stop and as this last moment of his life lingers on his final breath he’ll realise . . . he’ll realise that those beautiful scales had come from the skin of a fish . He’ll realise that the fishering mans determination and persistence had meant that his enduring hope had been fulfilled . Then he’ll sigh , his lungs will collapse and for the only the second time in his life he’ll smile from deep inside . And then he will die . He will be thirty one .

Chris Packham

. . . . .

Watch Chris’s video message

Following the story Chris delivered a video message about the television industry’s role in climate change. It was filmed on location in Tanzania.

View now »

Listen to the full lecture

Includes a Q&A where Chris talks in more detail about his ideas for change

Listen now »

The images on this page are copyright BAFTA/Jonny Birch and used with kind permission.